After the Great War, we drink “California Champagne”

My friends jokingly call me Benjamin when I serve Champagne or any other sparkling wine for that matter. Benjamin was Rob Lowe’s character in Paramount Picture’s 1992 film, Wayne’s World.

Rob Lowe as Benjamin in Paramount Picture’s Waynes World (1992)

In this film, Benjamin was attempting to demonstrate his “superiority” over Wayne, in front of his girlfriend, Cassandra. Benjamin states “actually, all Champagne is French. It’s the name of the region. Otherwise, it is sparkling white wine. Americans, of course, don’t recognize the convention so it becomes that thing of calling all their sparkling white Champagne, even though, by definition, they’re not.”

Now, I totally understand the point that the writers were driving home, but this statement is not entirely true. Americans were NOT calling all of their sparkling wines Champagne, and do we know the story behind why or even how “Americans don’t recognize the convention?”

Well, after this article you will.

Yes, even today, in 2024, there are Californian wineries that still label their sparkling wine as “Champagne,” but this is because of a government faux pas involving the Treaty of Versailles. (yes, I am referring to the peace agreement to end the Great War – World War 1). A war that ended over a hundred years ago (1919) is why we still have “California Champagne” today.

Do I have your attention now?

Great! Moving on

The War Faux Pas

For a bottle of sparkling wine to carry the name “Champagne” it MUST be made from the French region of Champagne, right? Well, not exactly.

Now these rules tend to be strictly enforced, but they are in fact not just rules, but rather regulations, laws and even explicitly written trade agreements between France and much of the world.

France began pushing for these laws in 1891. In 1891, the 23rd President Benjamin Harrison was in office, and he explicitly stated that the United States would not enter into any such agreement. The French were so determined to make other countries follow this law that they included this language into the Treaty of Versailles, which was a peace document signed to end the Great War/WW1.

Signing of The Treaty of Versailles (1919)

The language was specifically inserted into the Treaty because of French/German differences when it came to labelling wine. If you don’t believe me, then look at the French wine region of Alsace and their labelling. At the end of the Great War (World War 1), this peace agreement (Treaty of Versailles) was also signed by the United States. By signing this agreement, we too would have to abide by the request of not permitting any wine to use regional labelling from France. This would include the words such as Bourgogne (Burgundy), Chablis, Champagne, amongst others. The events that followed did not exactly go as planned.

After the war and after the Treaty was signed by all countries involved, the United States Senate failed to agree to the language and subsequently never ratified the Treaty or Versailles. Yes, you read that correctly, the Senate never ratified the Treaty that ended the first World War.

Shortly after this standoff, the United States enacted Prohibition, so truly…..no one cared that the Treaty was not ratified. The French were more worried about the loss of revenue from the lack of United States’ sales than whether some winery in California used the word Champagne. American wineries were all but dead anyway with the start of Prohibition.

When Prohibition ended in 1933, wine production in the United States was slow and truly did not pick up until the Judgement of Paris in 1976. This competition and their results were a huge boost for California wine production and therefore became, once again, a target of the French. This event brought back the argument of not calling sparkling wine “Champagne” unless it was from the French region of Champagne. But, as you recall, 60 years before the Judgement of Paris, the United States Senate never ratified the Treaty of Versailles.

In the 1980s, France and the United States reopened wine trade talks and finally, in 2005 the two countries came to an “agreement.” The United States would no-longer use terms such as Champagne on their wine labels unless …. And here it is….

Unless a producer was using “Champagne” on their label prior to March 10, 2006. If they were using that term prior to that date, they could use that term INDEFINITELY.

Making Benjamin’s statement from 1992’s Wayne’s World true when he said “Americans don’t recognize the convention.” However, the statement that all Americans called their sparkling wine Champagne was a gross generalization and truly incorrect. Don’t worry, I got you Wayne.

So, what makes Champagne so special?

Champagne

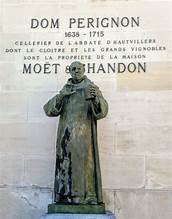

Contrary to popular belief, Dom Perignon did not invent sparkling wine. That designation has been given to the Monks of St. Hillaire, hundreds of miles south of the region Champagne yet still in France. Dom however is credited with the blending of the grapes during the process of making Champagne. This is known as the cuvée.

statue of the monk Dom Pèrignon

By law, Champagne is made from a combination of 3 possible grape varieties, two of which are red grapes – Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay, is the lone white grape variety. Therefore, if the Champagne is a “Blanc de Blanc” (white from white) then you know it is made from Chardonnay. If it is a “Blanc de Noir” (white from black) then it is made from either Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier or a combination of both, but it is NOT made with Chardonnay.

How a winery makes Champagne follows a multi-step process known as T\the Traditional method or The Champagne Method.

First, still wine is made (normal winemaking process) but typically with less sugar (Brix) than normal practice because the grapes will eventually undergo two separate fermentations in this process as opposed to other winemaking techniques. Once still wine is made, the wine is then blended which is called cuvée (Dom’s contribution). After the wines are blended together, the next step is called Prise de Mousse (seize the foam) which is the secondary fermentation that takes place within the bottle. At this time, the bottle is capped with your standard soda bottle/beer bottle looking metal cap (see below).

After the cap is placed, it is then placed into A-frame racks and slowly turned (riddling) every so often. (Yes, this is why it is called a riddling rack) The goal of this process is to collect all the dead yeast in the neck of the bottle.

yeast collected in the neck of a bottle

Once all the sediment/yeast is collected, the neck is then flash frozen, and that metal soda cap is quickly removed which shoots the frozen dead yeast out of the bottle. Once removed, a “liquor de dosage” (a small amount of liquid containing sugar and yeast) is added. The amount of sugar added here depends on the goal of sweetness the wine is seeking to achieve. Brut? Sec? demi-sec? After dosage is added, the bottle is placed in the cellar for aging – minimum 15 months for Non-Vintage Champagne and 3 years (yes 3 years) for Vintage Champagne.

So, if you see a bottle of Champagne with a year on the label, please know that it sat in their cellar for 3 years before it was allowed to be sold. So, a 2012 would not see the light of day (literally) until at least 2015 – keep in mind the 3 years is a MINIMUM not actually when it gets released. Wineries may choose to age their bottles longer.

Now, after all that, it is understandable why they would be protective of their product and their name. Other wineries making sparkling wine may use cheaper grapes, a less involved technique and certainly less of an aging requirement. (keep in mind all those years sitting and aging is costing the winery a fortune because it takes up space and no product is being sold) – typically why Vintage Champagne is much pricier than Non-Vintage Champagne.

So, if wineries aged their wines for less time because they needed to turn a profit for their wineries’ sustainability, the product may be less complex and have less flavors. Should they be permitted to use the moniker “Champagne” on the label? That does not seem ok, does it? Not at all, in my opinion.

All that being said, there are many other wine regions use the same method to make sparkling wine and very similar grapes, but again cannot use the name “Champagne.” One of those examples is Crémant.

Crémant

The entire world knows about Champagne, sure, but many do not realize that they also make sparkling wine in other regions within France. However, because of explicit wine laws, those regions’ sparkling wine is known as Crémant. One can find Crémant in regions such as Bordeaux, Alsace and even Bourgogne.

Crémant is also made in a similar manner to Champagne in fact calling the process, The Traditional Method or méthode champenoise (Champagne Method). Aging requirements are typically different, and the grapes utilized in the wine will vary by regional wine laws.

Crémant d’Alsace

Sparkling wine from the region of Alsace in northeast France. Per French wine laws, the grapes that can be utilized to make Crémant in this region are Pinot Blanc, Riesling, Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Pinot Noir or Auxerrois. Rosés are made only from Pinot Noir.

Crémant de Bourgogne

Sparkling wine from the region of Bourgogne in France. Per French wine laws, the grapes that can be utilized to make Crémant in this region are Chardonay, Pinot Noir from blanc and Rosés are allowed to use “up to” 20% Gamay. Aging requirements in this region are 9 months for general Crémant, 24 months for “eminent” and 36 months + 3 extra months in the cellar for “Grand Eminent.”

Crémant de Bordeaux

Sparkling wine from the region of Bordeaux in France. Per French wine laws, the grapes that can be utilized to make Crémant in this region invlude; Sauvignon Blanc, Sémillon, Muscadelle, Ugni Blanc and Colombard for blanc and Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Malbec, Petit Verdot and Carmenère for rosé. This region requires 9 months of aging .

Crémant d’Alsace - Crémant de Bourgogne - Crémant de Bordeaux

Conclusion

Though you may be having sparkling wine, you in fact may not be having specifically, Champagne. Other sparkling wines around the world include but are not limited to Prosecco, Lambrusco, Asti, Cava, Sekt.

Bottles of Champagne have been commanding higher premiums as of late, but keep in mind there are many alternative options, including those from nearby regions within France. These alternative options may not only include similar grapes but also similar methods in which it is made.

Similar grapes and similar method would generally command a similar taste would it not? Sometimes yes, but where you definitely notice a difference is in your pocketbook. Sometimes these similar wines will cost a fourth as much and have just as amazing flavor profiles. So, I urge you to not be afraid of the Crémants of France for they are truly diamonds in the rough.

You can find yours by clicking the picture below.

Cheers!